“Days come to me here when I rest in spirit, and am involuntarily glad. I sense the adequacy of the world, and believe that everything I need is here. I do not strain after ambition or heaven. I feel no dependence on tomorrow. I do not long to travel to Italy or Japan, but only across the river or up the hill into the woods.” — Wendell Berry, The Long-Legged House

Contrary to popular belief, New England’s seasonal year is not merely delineated into quarters, but is instead marked by innumerable “micro-seasons,” identified by unique phenological markers that often go by unnoticed. Though still technically summer, signs of autumn abound: the first species of asters and goldenrod have been blooming for at least a couple of weeks; groups of swallows and swifts that reared young further north pass through, joining lingering residents; synchronized mass hatchings of flying ants erupt in late afternoon and fill the neighborhood with shimmering wings in the westering sun.

Perhaps my favorite part of late-summer is the arrival of river fog. As the dark hours gradually lengthen and overnight temperatures assume a chillier edge, warm river water drifts from its channel and fills the valley with cocooning mist. Usually this is highly localized; hike up to 1,500’ just before dawn, and the last faint stars will still be visible as the eastern sky smolders into a cloudless sunrise, while the low country remains cloaked in a blanket of brume. By midmorning, with the sun’s ascent, the mist has evaporated, and only shady corners of the yard and the undersides of hemlock boughs remain dewy.

Although somewhat melancholy-inducing, this river-fog-season coincides with the earliest discernible color changes amongst trees and shrubs. These shifts usually begin in wetlands — environs where the soft maples and blueberry bushes turn fiery crimson when it is still skinny-dipping weather. Another species, itself a lover of long-lasting vernal pools and upland swamps, surely dons the most intense scarlet of all the deciduous woody plants of the Northeast — The black gum (Nyssa sylvatica), also called black tupelo or sourgum.1 To enjoy this tree’s spectacular fall foliage, one should search for it before traditional leaf-peeping season begins, and also venture into oft-maligned swamplands.

I had an urge for a good workout this past Saturday, and I wasn’t about to make a trip to the gym for a stint on the treadmill, coupled with a dumbbell session. No, I don’t do those things. Instead, I hopped on my bike for a quick pedal up the road and into the woods, where I stashed my ride, swapped clip-less boots for Chaco’s, and hoofed-it to where my real adventure started.

The topography here is rugged. To say the hills and ridges are steep is an understatement. Instead of gradually spaced contour lines, the elevation gradient on maps for my favorite haunts look like thick ribbons, or the bunched folds of a heavy, down comforter. Historical accounts document that these talus slopes once harbored the hibernaculum of timber rattlesnakes, and the numerous crevices and overhangs were surely denning sites for mountain lions centuries and millennia ago. Suffice it to say, one has to watch one’s footing when traversing this country, and in a wet summer like the one we’ve been having, rivulets and small waterfalls are everywhere, making the rocks even slicker.

As soon as I cut off trail and hit the ledges, I removed my sandals. I enjoy unimpeded exposure with the earth, and honestly, having direct contact with rocks and roots offers the best traction possible. Though not a sheer, vertical climb, I often end up utilizing my hands, and scamper up sections of ledge as a quadruped. My initial ascent took me from about 600’ to roughly 1,000’ in elevation. Soon the cascade of water I followed mellowed, and the raw bedrock began to be obscured by leaf littered pools where natural dams formed amid blowdown trees. Frogs kerr-plunked ahead of my approach, and tried to camouflage into the sediment, but I could see where their hind-sections were exposed. Moss growth abounds along this stretch, and my feet, admittedly a bit sore, luxuriated in the green softness.

In his book, Swampwalker’s Journal, David M. Carroll writes, “To have a bit of the landscape to oneself, to not be crowded in the landscape of this epoch, one is almost obliged to withdraw to a swamp.”2 After the arduous scramble I slowed my gait. A pileated woodpecker called from a short distance, then flew directly overhead before it vanished into the trees behind me. The breeze picked up slightly, and a woody tune, fiddle-like, vibrated where a hemlock limb rubs along an oak’s trunk — the junction of this connection polished smooth by years of friction. I belong to no church, subscribe to no religious doctrine, but this is truly holy land.

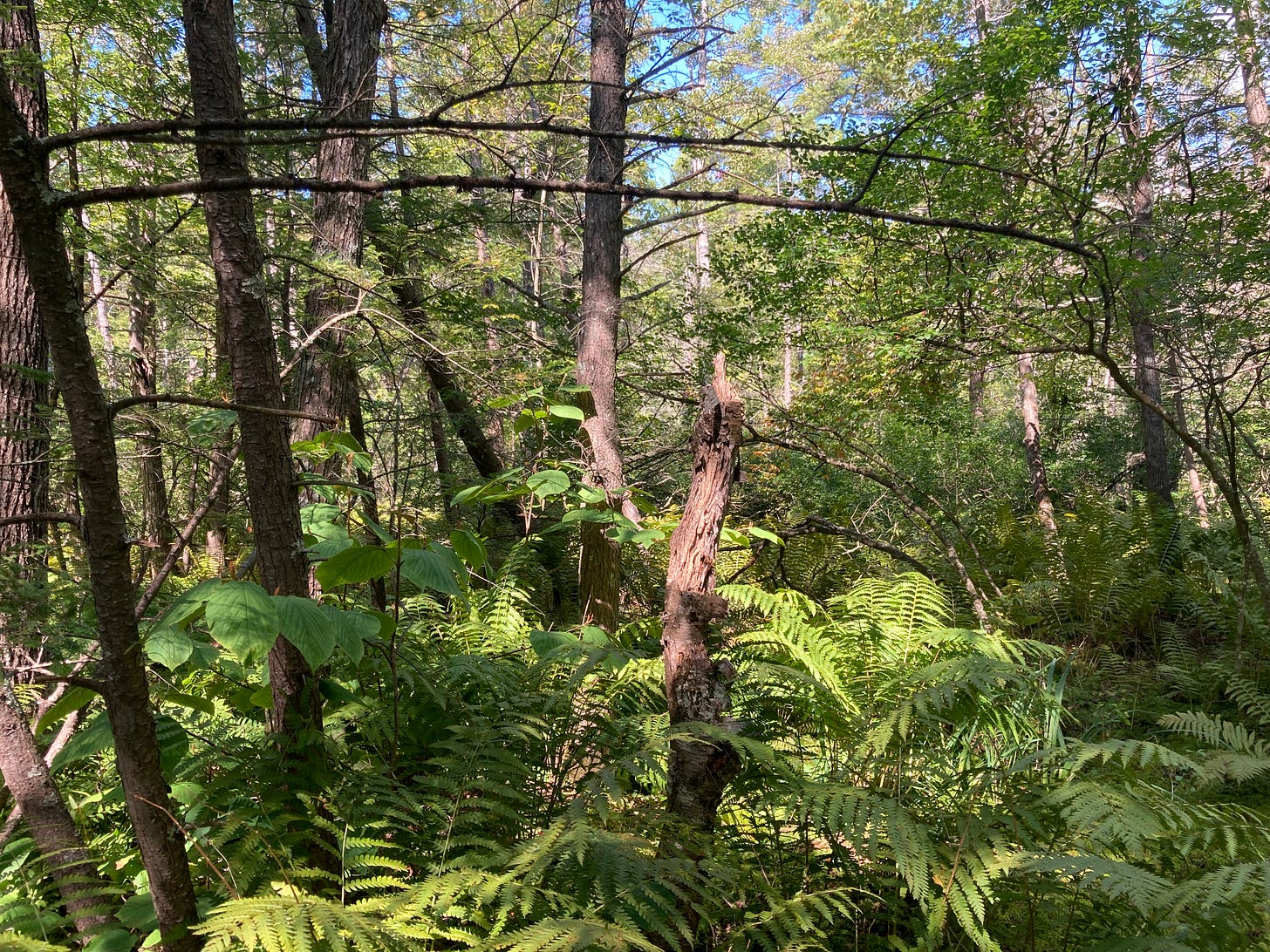

The stream-bed ended in an emerald carpet of sphagnum moss, sun-warmed and sensuous. What was fairly open woodland a moment before morphed into a thick, dense, almost claustrophobic jungle composed of an astonishingly biodiverse array of plants. Chest-high ferns, hobblebush, mountain laurel, winterberry, and spicebush forced me into primal yogic positions in order to contort my body around their branches. I noticed fresh deer tracks on my approach to the swamp margin, and sure enough, the quintessential “snort-wheeze” of a deer sounding the alarm echoed from the interior of the morass. There were additional paths threading through the understory, too wide to be deer, but just the right proportions to belong to black bear, and I wondered why the spoor appeared so fresh.

About eleven miles northwest — as the raven flies — is the Vernon Black Gum Swamp, in Vernon, VT. There are eight acres of protected swampland surrounded by an actively managed town forest. This small tract has been set aside from the logging occurring outside its boundaries because the swamp is home to a vestigial pocket of old growth black gums. Some years ago my father gave me a copy of The Sierra Club Guide to the Ancient Forests of the Northeast, by Bruce Kershner and Robert T. Leverett. Describing the Vernon Black Gum Swamp, they write, “Although only 18 to 36 inches in diameter, these trees are up to 435 years old. (Black gum trees attain the greatest longevity, 679 years of any broadleaf tree in eastern North America).”3 This book was published in 2004, so we can add another twenty years to those estimates, making the oldest black gum specimen, located in New Hampshire, at almost 700 years old.

These trees truly are specimens, whose Latin root, specere, means “to look.” One has to stand beside an ancient tupelo to appreciate and fully sense the numerous field identification marks which reveal great age. Kershner and Everett liken these old trees as having “alligator skin bark,” for as they grow in girth, their bark morphs from small checks and furrows, to deeply ridged armor. The widest elders sometimes display “baldness” on their trunks as well. Though not particularly tall for their age, sour gum crowns are often susceptible to wind, ice, and storm damage, giving them a gnarled, battle-worn appearance. This warrior metaphor is not merely poetical. Though its lumber has been used for a variety of products including shipping crates, tool handles, furniture, pulp, wheel hubs, shoe soles, ox-yokes, wharf piles, and rollers in glass factories, the wood of the black gum is difficult to split, heavy, incredibly tough, yet soft and not very durable, making it less than desirable for most practical purposes.4 While their fellow hardwood brethren fell to the axe and saw centuries ago, barring the majority of these other deciduous species old growth status, primeval black gums remain.

What is “useful” to people rarely concerns other creatures, though the inverse is often true. Black gums are dioecious, from the Greek, dioikía, meaning “two households,” and both male and female trees flower in early springtime, shortly after leaf emergence. These delicate yellow-green blooms are beloved by bees, and although I have not personally tried any, tupelo honey is purportedly quite delicious. After pollination, the female flowers morph into small fruits, which turn a deep, purply-blue in late-summer and early fall. William Cullina, in his book, Native Trees, Shrubs, and Vines, speculates that the “magnificent shades of scarlet, orange, apricot, maroon, and crimson,” are colored as such to attract birds to the fruit to aid in seed dispersal.5 Migrating thrush are die-hard enthusiasts, but many other birds, including wild turkey and ruffed grouse savor the thin-skinned drupes too.

After I jumped the bedded deer, I also disturbed a hermit thrush that had been devouring hobblebush fruit. Braced against the trunk of a hemlock snag to get a better look at the bird through my binoculars, it dawned on me why bears have been traveling through this particular swamp. As a bonafide omnivore, our local black bears feast on a variety of food items, including grubs they dislodge by tearing apart rotten logs, acorns and beech nuts, an occasional newborn deer fawn, and of course the plethora of berries and fruits native to this area. Tupelo fruit is one of their favorites. Certain seeds that pass through the digestive tracts of birds and mammals have higher germination success than those that remain uneaten. I wonder about the origins of the black gums in this swamp, and whether it was bird or bear, who aided in the planting of this magical haven, and what this ridge-top looked like two-hundred or more years ago.

Leaving the woods to return to the hustle and bustle of the modern world is always hard for me. I deliberately dragged my heels on this particular occasion, taking my time by composing additional photographs to document my outing. On my way downslope, I slipped on some wet moss and went for a short ride on my backside, coming to rest where a pile of rocks caught me. No blood or numbness. Full range of movement in my extremities. Just a bit of a crooked neck and tweaked shoulder. I figured the mountain wanted me to stay, or at least slow my pace even more to absorb the tranquility this special place offers. I shook myself like a wet dog to get the kinks out, then knelt on the forest duff layer, placed my forehead and hands on a particularly striking granite monolith, and thanked the hill for all it holds in its infinite steadfastness.

George A. Petrides and Janet Wehr, “A Field Guide to Eastern Trees,” (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1998), p. 60-61.

David M. Carrol, “A Swampwalker’s Journal: A Wetlands Year,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999), p. 126.

Bruce Kershner and Robert T. Leverett, “The Sierra Guide to the Ancient Forests of the Northeast, (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 2004), p. 230.

Charles Sprague Sargent, “Manual of The Trees of North America,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co, 1933), p. 781.

William Cullina, “Native Trees, Shrubs, and Vines: A Guide to Using, Growing, and Propagating North American Woody Plants,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2002), p. 176-177.

Beautiful piece to start my day. Brings me into the woods from my couch! thanks!!