Windchill

Noon. 19 degrees Fahrenheit. Winds west, northwest, steady at 17 mph, gusting to 33 — feels like three above zero. A frigid day for a walk. Long-johns: mandatory. Wool sweater, down jacket — check. I opt for two vests, and double-up on neck gaiters as well. Insulated Kinco’s mostly keep my fingers warm, but I still settle my hands in the vest pockets.

As I drive down the gravel road, dust devils dance in the river-bottom agricultural fields — an eery reminder that any form of industrial farming causes some degree of topsoil loss, no matter what the season, or attempted prevention measures.

I back the Tacoma off the road and park on the edge of a rhubarb planting, the field grown up in a matrix of weeds spared from cultivation and herbicide. The ground is frozen hard, like concrete. I hear the cheerful conversation of white-throated sparrows from a tangle of multiflora rose, speckled alder, and blackberry canes, near the edge of a small swamp.

The sun warms my face, and all the birds are clearly orienting their day around its presence. Further down the tractor-trace, I hear the melodious and unmistakable warble of tree sparrows, who mingle with the white-throats, all making short, dashing flights from field-edge-bramble to weedy rhubarb patch to feed on seeds.

A red-bellied woodpecker chuckles from the crown of a black walnut tree as I walk underneath, on my way to a back field, further away from the road. Upon entering this secluded opening, a spot where I’ve seen bobcats, a red-tailed hawk launches from its perch atop a riverside hickory. Two song sparrows flit out of a hummock of grass and vanish into thorny cover.

The worked-over field slopes gently toward the river. Irrigation equipment is staged in various places, and there is a crude path down the steep bank, where, during summer dry spells, huge pipes are laid into the water to feed center-pivot sprinkler systems half-a-mile away.

Swells of airborne dust swirl above the fields on the east side of the river, and at times I think I can taste the chalkiness. When the stronger gusts pick up, they carry the tan clouds away, toward the hills.

It is quiet here, aside from the wind, and a lone chickadee calling from a nearby box elder. Quiet, I should say, in terms of an absence of human-made noise. No freight train at this hour clacking over the steel bridge just upriver from my location. Perhaps I’ve subconsciously blocked out any overhead air traffic, or maybe the strong upper level winds are simply dispersing the engine roar beyond my level of hearing.

Instead, a comforting and ageless tune emanates from the water and ice-cover that has slowly formed over the last several weeks. I can’t help but liken it to the methodical creaking and groaning of a generations’-old rocking chair. Moments such as these make clear that rivers are living beings.

Part of me wants to curl up in the tall, tawny grass growing along the bank, stay, absorb the frail winter sun’s rays, and fall asleep to the river’s music. Instead, I grab hold of some woody sprigs of meadowsweet, firmly rooted in the frozen ground, wrap them around my hand, and hoist myself back over the eroded field’s edge.

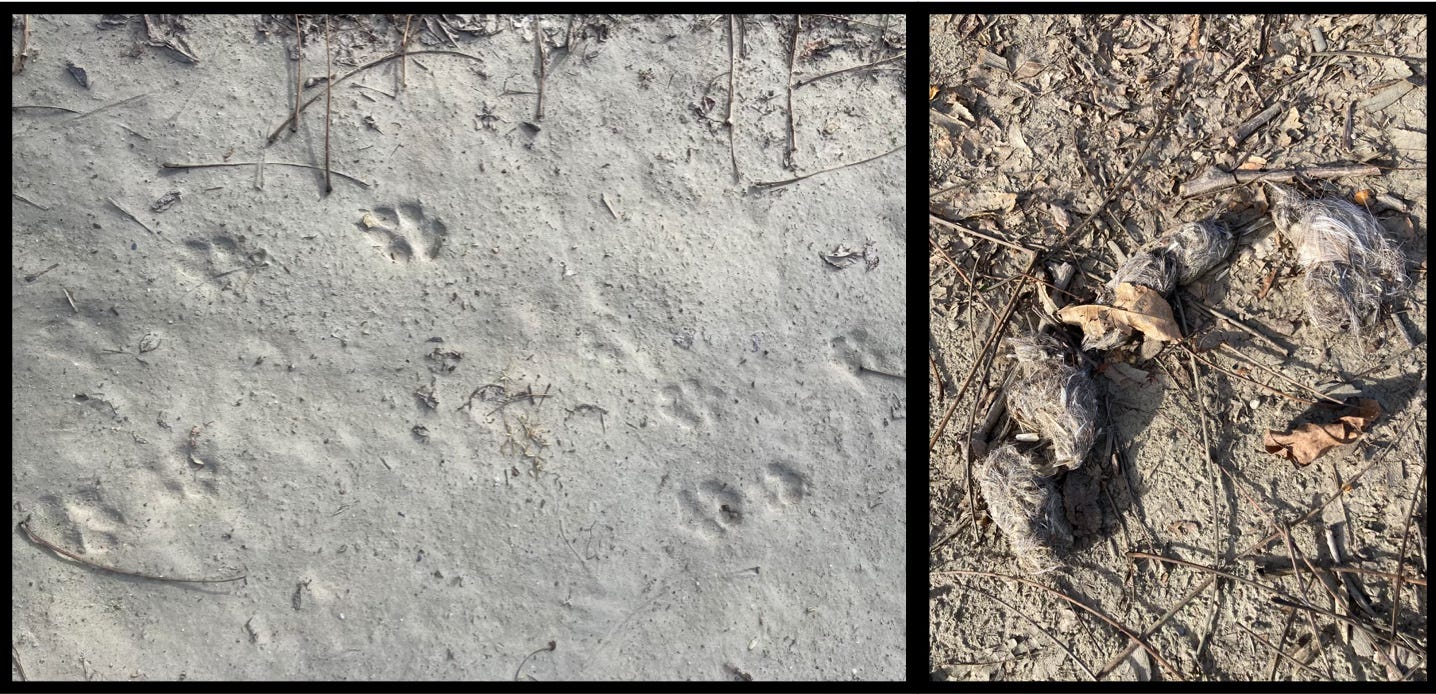

Sun behind me, wind in my face — it’s a cold walk back. I stay close to the river, and follow a string of coyote tracks made weeks ago when the ground was still muddy. Only a thin strip of hardwoods separates the farm field from the river, and I make short forays into the narrow copse, noting the freeze-dried droppings of cottontails, sign from what the coyotes were surely hunting.

More birds reveal themselves as I round the homestretch — juncos; bluebirds; robins; and a Carolina wren. A raven chortles from the north, making its way toward me. I bend down to inspect an island of ice in a depression of earth, peer out of the corner of my eye, and watch the raven attempt to tack into the wind, aiming to investigate what I am up to.

The bird quickly dismisses me and wheels off into crystalline sky. Hedge-row-foraging songbirds flutter nervously away from my advances, despite declarations of benevolence. I don’t want to interrupt their feeding and sunning during the sun’s apex, so I hoof-it the last couple of hundred yards.

Hopping into the truck’s cab, I suddenly feel quite chilled, despite my multi-layered cold-weather gear. To say I admire and respect the wildlife living their whole lives immersed in the elements, though truthful, would still be a profound understatement. Perhaps it would be more honest to acknowledge the envy I feel, sensing the raw freedom they experience within the cosmos that pulses through their beautiful bodies.

I offer a silent prayer to these creatures, thanking them for the glimpses they present, demonstrating that we too, can embody an unbroken connection to the wild.